GENUS -Nymphaea – Waterlilies Joel Plumb

Family - NYMPHAEACEAE

Worldwide some 50 or more species.

in Queensland - 10 species (2 exotic)

NomenclatureNymphaea - in Greek and Roman mythology nymphs were beautiful maidens of a lesser divinity who

lived in groves, forests, springs, fountains, streams, lakes, mountains, oceans etc and thus the name has been applied botanically to water lilies.

Species recorded in Rockhampton/Capricorn Coast area

Nymphaea caerulea var zanzibarensis (E)

Nymphaea gigantea var gigantea

Nymphaea immutabilis

Nymphaea mexicana (E)

Nymphaea nouchali

Characteristics of the genus

Form Aquatic plants with creeping rhizomes or tuberous stems rooting in the mud at the bottom of the pool.

Leaves Flat, round to heart-shaped, small to large, thin or thick, green to reddish-green, floating on the surface of the water attached to long petioles.

Flowers Large, showy, variously coloured, on or raised above the water surface on long stout peduncles; sepals

3-5 (usually 4), petals 6-50.

Fruits Ripening under water, fleshy, capsule-like; seeds embedded in a gelatinous substance which keeps them afloat for a time after dehiscing from capsule.

Some usesWaterlilies were an important food item for many aboriginal tribes - flowers were eaten raw as were stems and stalks after peeling, young tuberous stems were baked, seeds were baked in the pods and eaten or ground up to make cakes or loaves.

Waterlilies have long been popular horticulturally in ponds and water features.

An unusual custom recorded in some tribes by Sir Baldwin Spencer was that front teeth when knocked out as part of a ceremony were buried beside a lagoon or water hole to make the waterlilies grow.

Field note

The more common Nymphaea species encountered locally are (a) Nymphaea caerulea var zanzibarensis and (b) Nymphaea gigantea, the following tips should aid in identification.

(a)petal apices pointed; anthers curving towards flower centre; terminal anther appendages same colour as petals (b)petal apices rounded; anthers straight upright; terminal anther appendages yellow

Recorded wildlife connections with NymphaeaBirds recorded feeding on Nymphaea species

darter, magpie goose, plumed whistling duck, wandering whistling duck, black swan, green pygmygoose, cotton pygmy-goose, grey teal, Pacific black duck, hardhead, dusky moorhen, Eurasian coot and whiskered tem.

Insects recorded associating with Nymphaea species

Donacia beetle species, the larvae of which, can pierce plant roots to obtain air.

Monday, December 19, 2005

The Pittosporum genus Joel Plumb

The genus consists of evergreen trees and shrubs , sometimes spiny, belonging to the PITTOSPORACEAE family.

Some 150+ species occur in tropical and subtropical parts of Africa, Asia, Australia and New Zealand.

Pittosporum is derived from Greek words pitta pitch and spora seed, a reference to the sticky substance surrounding the seeds.

Characteristics of the genus

Leaves usually petiolate, simple, alternate or whorled, without stipules; margins entire or with small teeth.

Flowers small and bell-like, solitary or in various inflorescences, often perfumed; sepals 5; petals 5; stamens 5, alternating with petals.

Fruits dehiscent capsules; valves leathery or hard; seeds usually immersed in a sticky fluid.

Queensland Pittosporum species

P angustifolium (formerly P. phylliraeoides) #

P .ferrugineum ssp ferrugineum

P. ferrugineum ssp linifolium #

P .lancifolium (formerly Citriobatus lancifolius)

P. multiflorum (formerly Citriobatus pauciflorus)

P. oreillyanum

P. revolutum #

P. rubiginosum

P. spinescens (formerly Citriobatus spinescens) #

P. trilobum

P. undulatum

P. venulosum #

P. viscidum (formerly Citriobatus linearis)

P. wingii

# These species found in the Rockhampton/Capricorn Coast area.

N.B. Pittosporum rhombifolium is now Auranticarpa

Rhombifolia #

Pittosporum uses past and present

P. angustifolium Stock will browse on the foliage which has been used as a drought fodder. Some aboriginal tribes treated pains and cramping by drinking an infusion of the seeds, fruit pulp, leaves or wood. After boiling the fruit in water the liquid was drunk or applied to treat skin inflammations and itches. It was also used for colds and to promote the secretion of breast milk.

Some tribes pounded the bitter seed to make a flour.

The gum is reported to be edible.

P. revolutum The leaves contain saponin and may be used as a substitute for soap.

P. spinescens The fruit was eaten by some aboriginal tribes

P. venulosum Bruised roots placed near the shelters of aboriginal women gave off an aromatic odour which reportedly sexually excited the women.

Recorded Pittosporum wildlife connections

Leaf and/or foliage feeders The larvae of the bright copper

(P. multiflorum) and fiery copper (P. spinescens) butterflies and thrip species which cause leaf galls.

Flower and/or nectar and/or pollen feeders Grey-headed flying-foxes (P. undulatum), Australian ringneck parrots

(P. angustifolium) and Lewin's (P. undulatum) and yellow-plumed (P. angustifolium) honeyeaters.

Fruit and/or seed eaters Grey-headed flying-foxes (P. undulatum), southern cassowaries (P. rubiginosum), Lewin's

(P. multiflorum, P. undulatum), spiny-cheeked (P. angustifolium) and singing (P. angustifolium) honeyeaters, malleefowl (genus only), white-headed pigeons (P. undulatum), superb fruit-doves (P. undulatum), Major Mitchell's cockatoos (P. angustifolium), Australian ringneck parrots (P. angustifolium), red wattlebirds (P. angustifolium), pilotbirds (genus only),

silvereyes (P. undulatum, P. angustifolium), pied currawongs

(P. undulatum), satin bowerbirds (genus only), dusky woodswallows (genus only) and bright cornelian butterfly larvae

(P. undulatum).

Some hopefully helpful distinguishing features between P. Ferrugineum and P. Venulosum

Feature P. Ferrugineum P. Venulosum

Leaf apex bluntly pointed drawn out to a more acute point

Leaf base somewhat attenuate cuneate

Angle of lateral veins to midrib approximately 45 degrees approximately 60 degrees

No. of lateral veins usually less than 8 per side usually 8 or more per side

New growth pale fawn rusty brown

Seeds grouped into amalgamated up to 14 or so and separate

bundles

The genus consists of evergreen trees and shrubs , sometimes spiny, belonging to the PITTOSPORACEAE family.

Some 150+ species occur in tropical and subtropical parts of Africa, Asia, Australia and New Zealand.

Pittosporum is derived from Greek words pitta pitch and spora seed, a reference to the sticky substance surrounding the seeds.

Characteristics of the genus

Leaves usually petiolate, simple, alternate or whorled, without stipules; margins entire or with small teeth.

Flowers small and bell-like, solitary or in various inflorescences, often perfumed; sepals 5; petals 5; stamens 5, alternating with petals.

Fruits dehiscent capsules; valves leathery or hard; seeds usually immersed in a sticky fluid.

Queensland Pittosporum species

P angustifolium (formerly P. phylliraeoides) #

P .ferrugineum ssp ferrugineum

P. ferrugineum ssp linifolium #

P .lancifolium (formerly Citriobatus lancifolius)

P. multiflorum (formerly Citriobatus pauciflorus)

P. oreillyanum

P. revolutum #

P. rubiginosum

P. spinescens (formerly Citriobatus spinescens) #

P. trilobum

P. undulatum

P. venulosum #

P. viscidum (formerly Citriobatus linearis)

P. wingii

# These species found in the Rockhampton/Capricorn Coast area.

N.B. Pittosporum rhombifolium is now Auranticarpa

Rhombifolia #

Pittosporum uses past and present

P. angustifolium Stock will browse on the foliage which has been used as a drought fodder. Some aboriginal tribes treated pains and cramping by drinking an infusion of the seeds, fruit pulp, leaves or wood. After boiling the fruit in water the liquid was drunk or applied to treat skin inflammations and itches. It was also used for colds and to promote the secretion of breast milk.

Some tribes pounded the bitter seed to make a flour.

The gum is reported to be edible.

P. revolutum The leaves contain saponin and may be used as a substitute for soap.

P. spinescens The fruit was eaten by some aboriginal tribes

P. venulosum Bruised roots placed near the shelters of aboriginal women gave off an aromatic odour which reportedly sexually excited the women.

Recorded Pittosporum wildlife connections

Leaf and/or foliage feeders The larvae of the bright copper

(P. multiflorum) and fiery copper (P. spinescens) butterflies and thrip species which cause leaf galls.

Flower and/or nectar and/or pollen feeders Grey-headed flying-foxes (P. undulatum), Australian ringneck parrots

(P. angustifolium) and Lewin's (P. undulatum) and yellow-plumed (P. angustifolium) honeyeaters.

Fruit and/or seed eaters Grey-headed flying-foxes (P. undulatum), southern cassowaries (P. rubiginosum), Lewin's

(P. multiflorum, P. undulatum), spiny-cheeked (P. angustifolium) and singing (P. angustifolium) honeyeaters, malleefowl (genus only), white-headed pigeons (P. undulatum), superb fruit-doves (P. undulatum), Major Mitchell's cockatoos (P. angustifolium), Australian ringneck parrots (P. angustifolium), red wattlebirds (P. angustifolium), pilotbirds (genus only),

silvereyes (P. undulatum, P. angustifolium), pied currawongs

(P. undulatum), satin bowerbirds (genus only), dusky woodswallows (genus only) and bright cornelian butterfly larvae

(P. undulatum).

Some hopefully helpful distinguishing features between P. Ferrugineum and P. Venulosum

Feature P. Ferrugineum P. Venulosum

Leaf apex bluntly pointed drawn out to a more acute point

Leaf base somewhat attenuate cuneate

Angle of lateral veins to midrib approximately 45 degrees approximately 60 degrees

No. of lateral veins usually less than 8 per side usually 8 or more per side

New growth pale fawn rusty brown

Seeds grouped into amalgamated up to 14 or so and separate

bundles

The genus Utricularia (Bladderworts)

Utricularia belong to the Lentibulariaceae family and worldwide there are some 300 species.

19 species have been identified in Queensland and 11 of these are known to occur in the Port Curtis Pastoral District.

The genus name is derived from the Latin word utriculus meaning a small bladder - an appropriate name as species in this genus possess small insect-trapping sacs which may occur on emergent or subterranean or submerged parts of the plant.

These small carnivorous plants may be aquatic or reside in boggy situations beside swamps and waterholes.

The leaves on terrestrial species are very small near ground level or apparently absent while those of the aquatic species are divided into hair-like segments.

Flower colours are usually yellow, white, red, blue or purple but as most plants are quite small they need to be examined closely to be really appreciated. However, some plants congregate into colonies and when flowering can create quite a pleasing splash of colour. The lower corolla lip of most species is comparatively large often with throat markings.

The tiny dehiscent fruits have persistent calyces which often increase with age.

Utricularia trap their prey in small bladders whose walls are equipped with tiny gland-like structures that evacuate the water from inside and create a partial vacuum. Tiny organisms are enticed towards the trapdoor entrance by secreted attractants and/or directional antennae-like appendages. Here, trigger-like sensory hairs, when touched fling the trapdoor open. Prey and water are engulfed within the bladder and with the trapdoor closing behind the digestion stage may now commence. And so, in time, the process repeats itself.

Not much information exists regarding the place of Utricularia in the food chain but green pygmy geese and wandering whistling ducks have been recorded feeding on Utricularia as, no doubt, many other creatures do.

Many Utricularia species may be grown in pots sitting in water and make interesting subjects.

The following are some Port Curtis species and their flower colours - U. aurea (yellow),

U bifida (blue/white), U. biloba (dark blue), U. caerulea (purple/blue/mauve/white),

U. chrysantha (yellow), U dichotoma (deep violet), U. gibba (yellow), U. lateriflora (pale mauve/white/reddish-purple), Uliginosa (blue/white/mauve/violet).

Joel Plumb

Utricularia belong to the Lentibulariaceae family and worldwide there are some 300 species.

19 species have been identified in Queensland and 11 of these are known to occur in the Port Curtis Pastoral District.

The genus name is derived from the Latin word utriculus meaning a small bladder - an appropriate name as species in this genus possess small insect-trapping sacs which may occur on emergent or subterranean or submerged parts of the plant.

These small carnivorous plants may be aquatic or reside in boggy situations beside swamps and waterholes.

The leaves on terrestrial species are very small near ground level or apparently absent while those of the aquatic species are divided into hair-like segments.

Flower colours are usually yellow, white, red, blue or purple but as most plants are quite small they need to be examined closely to be really appreciated. However, some plants congregate into colonies and when flowering can create quite a pleasing splash of colour. The lower corolla lip of most species is comparatively large often with throat markings.

The tiny dehiscent fruits have persistent calyces which often increase with age.

Utricularia trap their prey in small bladders whose walls are equipped with tiny gland-like structures that evacuate the water from inside and create a partial vacuum. Tiny organisms are enticed towards the trapdoor entrance by secreted attractants and/or directional antennae-like appendages. Here, trigger-like sensory hairs, when touched fling the trapdoor open. Prey and water are engulfed within the bladder and with the trapdoor closing behind the digestion stage may now commence. And so, in time, the process repeats itself.

Not much information exists regarding the place of Utricularia in the food chain but green pygmy geese and wandering whistling ducks have been recorded feeding on Utricularia as, no doubt, many other creatures do.

Many Utricularia species may be grown in pots sitting in water and make interesting subjects.

The following are some Port Curtis species and their flower colours - U. aurea (yellow),

U bifida (blue/white), U. biloba (dark blue), U. caerulea (purple/blue/mauve/white),

U. chrysantha (yellow), U dichotoma (deep violet), U. gibba (yellow), U. lateriflora (pale mauve/white/reddish-purple), Uliginosa (blue/white/mauve/violet).

Joel Plumb

The genus Amyema - A genus of mistletoes

Amyema belong to the Loranthaceae family which, with the Viscaceae family, contain most species commonly referred to as mistletoes.

The name Amyema is derived from the Greek a- (a negative prefix) and myeo (I initiate). This refers to the fact that this genus was previously not recognized as a separate entity as it and several other mistletoe genera had formerly been grouped under Loranthus.

Some 100 or so Amyema species are distributed from Malaya, the Philippines, New Guinea and Australia to the western Pacific. Some 36 species occur in Australia of which 32 are endemic. 24 species of the genus have been identified in Queensland and of these 9 species have been recorded in Port Curtis.

Port Curtis species and common hosts

A.biniflorum eucalypts

A.cambagei Casuarina species

A.congener ssp congener rainforest species

ssp rotundifolium Acacia, Casuarinaceae & Geyeraparviflora

A.conspicuum ssp conspicuum Alphitonia & Acacia

A.mackayense mangroves

A.miquelii eucalypts & Acacia

A.pendulum ssp longifolium eucalypts & Acacia

A.quandang var bancroftii on many Acacia species

A.sanguineum var sanguineum mostly eucalypts

Amyema genus characteristics

Erect to pendulous, aerial, stem-parasitic shrubs attached to their host by woody haustoria (absorbing organs through which a parasite obtains chemical substances from its host); epicortical (outside of but on the bark) runners present or absent.

Leaves usually opposite or near-opposite and entire.

Inflorescences made up of umbel (a type of wheel-like inflorescence) of dyads (groups of 2), triads (groups of 3) or tetrads (groups of 4) or sometimes reduced to simple umbel or head.

Flowers with 4-6 petals separated to the base and which shed separately and basifixed (attached at the bottom) anthers.

Fruits baccate (berry-like); single seed surrounded by sticky layer.

Many species tend to mimic the appearance of their hosts.

Amyema uses

The sticky fruits are edible.

Some aboriginal tribes bruised the leaves of A. quandang in water and then drank the water as a treatment for fevers.

In some tribes both men and women boiled the mucilaginous fruits of A. maidenii in water and drank the decoction to treat inflammations of the genital area. That amount which would go into a hollowed hand was taken three times a day.

Amyema and wildlife

Amyema flowers, flower buds, nectar, pollen, leaves, fruits, seeds, bark and sterns play a very important role in sustaining many animal species.

Wildlife recorded feeding on various Amyema species includes

72 bird species (mostly belonging to the parrot and honeyeater clans).

The larvae of 18 butterfly species (mostly jezebels, jewels and azures).

The larvae of 8 moth species Joel Plumb

Amyema belong to the Loranthaceae family which, with the Viscaceae family, contain most species commonly referred to as mistletoes.

The name Amyema is derived from the Greek a- (a negative prefix) and myeo (I initiate). This refers to the fact that this genus was previously not recognized as a separate entity as it and several other mistletoe genera had formerly been grouped under Loranthus.

Some 100 or so Amyema species are distributed from Malaya, the Philippines, New Guinea and Australia to the western Pacific. Some 36 species occur in Australia of which 32 are endemic. 24 species of the genus have been identified in Queensland and of these 9 species have been recorded in Port Curtis.

Port Curtis species and common hosts

A.biniflorum eucalypts

A.cambagei Casuarina species

A.congener ssp congener rainforest species

ssp rotundifolium Acacia, Casuarinaceae & Geyeraparviflora

A.conspicuum ssp conspicuum Alphitonia & Acacia

A.mackayense mangroves

A.miquelii eucalypts & Acacia

A.pendulum ssp longifolium eucalypts & Acacia

A.quandang var bancroftii on many Acacia species

A.sanguineum var sanguineum mostly eucalypts

Amyema genus characteristics

Erect to pendulous, aerial, stem-parasitic shrubs attached to their host by woody haustoria (absorbing organs through which a parasite obtains chemical substances from its host); epicortical (outside of but on the bark) runners present or absent.

Leaves usually opposite or near-opposite and entire.

Inflorescences made up of umbel (a type of wheel-like inflorescence) of dyads (groups of 2), triads (groups of 3) or tetrads (groups of 4) or sometimes reduced to simple umbel or head.

Flowers with 4-6 petals separated to the base and which shed separately and basifixed (attached at the bottom) anthers.

Fruits baccate (berry-like); single seed surrounded by sticky layer.

Many species tend to mimic the appearance of their hosts.

Amyema uses

The sticky fruits are edible.

Some aboriginal tribes bruised the leaves of A. quandang in water and then drank the water as a treatment for fevers.

In some tribes both men and women boiled the mucilaginous fruits of A. maidenii in water and drank the decoction to treat inflammations of the genital area. That amount which would go into a hollowed hand was taken three times a day.

Amyema and wildlife

Amyema flowers, flower buds, nectar, pollen, leaves, fruits, seeds, bark and sterns play a very important role in sustaining many animal species.

Wildlife recorded feeding on various Amyema species includes

72 bird species (mostly belonging to the parrot and honeyeater clans).

The larvae of 18 butterfly species (mostly jezebels, jewels and azures).

The larvae of 8 moth species Joel Plumb

The Ficus aenus - The Figs

Belonging to the Moraceae family, this genus takes its name from an old Latin word used to name the fig tree (Ficus carica).

Worldwide some 1 000 or so species occur mostly in tropical. and warm temperate regions. Of the 50 or so species found in Australia, some 38 species (3 exotic, 1 unnamed) have been identified in Queensland.

Ficus species recorded in the Rockhampton/Capricom Coast area include - F adenosperma, F. benghalensis, F. congesta var congest a, F copiosa, F. coronata, F. fraseri, varieties of F. microcarpa, F. obliqua, varieties of F. opposita, F. racemosa var racemosa, F. rubiginosa (which now includes F. baileyana, F. ob/iqua var patio/aris and except for Nth Q'ld F. platypoda), F. superba var henneana and varieties of F. virens.

Ficus species are latex-bearing and may be evergreen, deciduous or partly so. They may be trees, shrubs, banyans, epiphytic climbers or root climbers (none locally). Many have buttressed trunks. Figs are some of the world's largest trees - one species of Ficus benghalensis in India is reputed to be almost a kilometre in circumference.

Ficus leaves - petiolate, alternate, sometimes opposite, sometimes distichous, sometimes decussate, simple, entire or toothed or palmately-lobed, often glandular - on leaf undersurface or in vein axils or at petiole apex, stipular with stipules being free and paired or joined and stem-clasping.

Ficus flowers - tiny, unisexual, enclosed inside small hollow receptacle which has an even smaller flapped opening (ostiole). Flowers of 3-4 types - male (1-8 stamens), female, sterile male (neuter) and sterile female (gall flower) inhabited by fig-wasp.

Ficus fruit - drupe-like, varied in shape, often paired, sometimes clustered; may be axillary, cauliflorous (on trunk or major branches), ramiflorous (on recently formed woody branches) or geocarpic (fruiting on trunk runners which root in the ground).

Waso/fia svmbiotic relationshios

Adult female agaonid wasps are essential pollinators of Ficus flowers, they are highly host-specific, each species usually being restricted to 1 species of Ficus. The wing-reduced males usually mate and die without leaving the fig. The larvae feed on developing Ficus ovules. The larvae of other nonpollinating wasp species may also be present.

Some notes on the genus

Ficusin construction

The timber is pale-coloured, soft, light-weight, quick to decay and has been used sparingly to make packing-cases. F. elastica latex was used for rubber-making before it was replaced by the Brazilian rubber tree, Hevea brasiliensis (Euphorbiaceae). A disadvantage of the former was that its latex could be harvested only every third year. Aboriginal uses included - making canoes from the bark of some species; making dilly-bags and fishing nets from the inner fibrous bark and in the Brisbane area from the roots of F. macrophylla; in Nth Queensland pounding the inner bark of

F. pleurocarpa & F. variegata to make bark blankets similar in texture to Polynesian tapa cloth; using the plank buttresses of some species as shields; smoothing down implements and weapons with the sandpapery leaves of some species. In some areas the women used these rough leaves to remove hairs from their legs.

Ficus in medicine

Some aboriginal tribes used F. coronata latex to disinfect wounds which were often then covered with a poultice of scraped Grewia root.

F. opposita latex was applied to ringworms or rubbed on hands to prevent diarrhoea. In India medicinal use of F. racemosa included - treating mumps, gonorrhoea and other inflammations with the latex; taking the root-juice as a tonic; using the astringent qualities of bark and fruit to treat bloody urine, excessive menstrual bleeding and coughing up blood and taking milk-soaked leaf galls mixed with honey to control smallpox pitting.

Ficus as food

All figs are edible, F. coronata, F. opposits, F. racemosa, F. atkinsiana being some that are more palatable. Aborigines ate them raw or collected dry fruit for storage while early settlers often made jam from the fruit.

F. racemosa is particularly rich in calcium (40mg per gram as compared to milk's 2mg per gram).

Most young fig shoots can be used as a boiled green vegetable; older leaves are readily eaten by grazing animals. Aboriginal tribes of the Tully area used the sticky latex of a fig species as birdlime to snare small birds.

Ficus in horticulture

Fig trees are ideal in parks, botanic gardens etc but generally speaking are too large and too root invasive for average home gardens.

Many species make fine indoor and tub plants for at least part of their lives.

Significance in the wildlife foodchain

Ficus fruit, seeds, leaves, flowers, shoots and bark play important roles in providing sustenance for an incredible array of animal species. Wildlife observations and surveys have indicated that the following numbers are known to feed on the Ficus genus - 17 mammal species, 89 birds species, 3 butterfly larvae and 14 moth larvae. The genus also hosts a myriad of insects including flies, beetles, thrips, psyllids, bugs and wasps.

Joel Plumb

Belonging to the Moraceae family, this genus takes its name from an old Latin word used to name the fig tree (Ficus carica).

Worldwide some 1 000 or so species occur mostly in tropical. and warm temperate regions. Of the 50 or so species found in Australia, some 38 species (3 exotic, 1 unnamed) have been identified in Queensland.

Ficus species recorded in the Rockhampton/Capricom Coast area include - F adenosperma, F. benghalensis, F. congesta var congest a, F copiosa, F. coronata, F. fraseri, varieties of F. microcarpa, F. obliqua, varieties of F. opposita, F. racemosa var racemosa, F. rubiginosa (which now includes F. baileyana, F. ob/iqua var patio/aris and except for Nth Q'ld F. platypoda), F. superba var henneana and varieties of F. virens.

Ficus species are latex-bearing and may be evergreen, deciduous or partly so. They may be trees, shrubs, banyans, epiphytic climbers or root climbers (none locally). Many have buttressed trunks. Figs are some of the world's largest trees - one species of Ficus benghalensis in India is reputed to be almost a kilometre in circumference.

Ficus leaves - petiolate, alternate, sometimes opposite, sometimes distichous, sometimes decussate, simple, entire or toothed or palmately-lobed, often glandular - on leaf undersurface or in vein axils or at petiole apex, stipular with stipules being free and paired or joined and stem-clasping.

Ficus flowers - tiny, unisexual, enclosed inside small hollow receptacle which has an even smaller flapped opening (ostiole). Flowers of 3-4 types - male (1-8 stamens), female, sterile male (neuter) and sterile female (gall flower) inhabited by fig-wasp.

Ficus fruit - drupe-like, varied in shape, often paired, sometimes clustered; may be axillary, cauliflorous (on trunk or major branches), ramiflorous (on recently formed woody branches) or geocarpic (fruiting on trunk runners which root in the ground).

Waso/fia svmbiotic relationshios

Adult female agaonid wasps are essential pollinators of Ficus flowers, they are highly host-specific, each species usually being restricted to 1 species of Ficus. The wing-reduced males usually mate and die without leaving the fig. The larvae feed on developing Ficus ovules. The larvae of other nonpollinating wasp species may also be present.

Some notes on the genus

Ficusin construction

The timber is pale-coloured, soft, light-weight, quick to decay and has been used sparingly to make packing-cases. F. elastica latex was used for rubber-making before it was replaced by the Brazilian rubber tree, Hevea brasiliensis (Euphorbiaceae). A disadvantage of the former was that its latex could be harvested only every third year. Aboriginal uses included - making canoes from the bark of some species; making dilly-bags and fishing nets from the inner fibrous bark and in the Brisbane area from the roots of F. macrophylla; in Nth Queensland pounding the inner bark of

F. pleurocarpa & F. variegata to make bark blankets similar in texture to Polynesian tapa cloth; using the plank buttresses of some species as shields; smoothing down implements and weapons with the sandpapery leaves of some species. In some areas the women used these rough leaves to remove hairs from their legs.

Ficus in medicine

Some aboriginal tribes used F. coronata latex to disinfect wounds which were often then covered with a poultice of scraped Grewia root.

F. opposita latex was applied to ringworms or rubbed on hands to prevent diarrhoea. In India medicinal use of F. racemosa included - treating mumps, gonorrhoea and other inflammations with the latex; taking the root-juice as a tonic; using the astringent qualities of bark and fruit to treat bloody urine, excessive menstrual bleeding and coughing up blood and taking milk-soaked leaf galls mixed with honey to control smallpox pitting.

Ficus as food

All figs are edible, F. coronata, F. opposits, F. racemosa, F. atkinsiana being some that are more palatable. Aborigines ate them raw or collected dry fruit for storage while early settlers often made jam from the fruit.

F. racemosa is particularly rich in calcium (40mg per gram as compared to milk's 2mg per gram).

Most young fig shoots can be used as a boiled green vegetable; older leaves are readily eaten by grazing animals. Aboriginal tribes of the Tully area used the sticky latex of a fig species as birdlime to snare small birds.

Ficus in horticulture

Fig trees are ideal in parks, botanic gardens etc but generally speaking are too large and too root invasive for average home gardens.

Many species make fine indoor and tub plants for at least part of their lives.

Significance in the wildlife foodchain

Ficus fruit, seeds, leaves, flowers, shoots and bark play important roles in providing sustenance for an incredible array of animal species. Wildlife observations and surveys have indicated that the following numbers are known to feed on the Ficus genus - 17 mammal species, 89 birds species, 3 butterfly larvae and 14 moth larvae. The genus also hosts a myriad of insects including flies, beetles, thrips, psyllids, bugs and wasps.

Joel Plumb

The ELAEOCARPACEAE family

This family of tropical and subtropical trees and shrubs is predominantly rainforest dwelling.

Worldwide there are some 12 or more genera and more than 350 species. The family name reflects that of one important genus, Elaeocarpus, whose name is derived from Greek words meaning 'olive-like fruit' - seemingly more appropriate for some ELAEOCARPACEAE genera than others.

Some of the family's characteristics -

Leaves alternate or opposite, with stipules; margins entire or toothed; occasionally domatia evident. Flowers bisexual; petals 4-5 or absent altogether, often fringed; stamens numerous.

Fruits capsular in some genera, drupaceous in others.

ELAEOCARPACEAE genera in Queensland

Aceratium 5 species, all found in N.E. Queensland.

Dubouzetia I species, a small cliff-dweller found near Townsville and classified 'vulnerable'.

Elaeocarpus 25 species (5 as yet unnamed), some Q'Id species also occurring in NT and NSW.

Peripentadenia 2 species, both from N.E. Queensland, both classified 'rare'.

Sloanea 4 species, 2 Q'Id species also found in NSW.

ELAEOCARPACEAE representatives in the Rockhamton/Capricom Coast area

Elaeocarpus eumundi - usually in gallery rainforest communities

Elaeocarpus grandis - usually in gallery rainforest communities

Elaeocarpus obovatus - usually in dry rainforest communities

Elaeocarpus reticulatus - recorded from the Shoalwater Bay area

Sloanea langii - in gallery rainforest, reaching its southern distribution limit at Byfield.

Elacocrpus and Sloanea uses

Elaeocarpus and Sloanea timber is generally light-weight, soft and pale-coloured and has been used internally for furniture, flooring, joinery, plywood and lining and for case-making.

The pitted stones of E. grandis have been gathered and used to make necklaces.

The kernels of some Elaeocarpus, e.g. E. bancroftii, have been used as food by both aborigines and early settlers.

The gum of S. australis is reported to have been used in New South Wales as a stiffener for straw hats.

E. reticulatus (blueberry ash) is often cultivated as an ornamental.

Various species of Elaeocarpus and/or Sloanea provide food for mammals, birds, butterfly larvae, moth larvae and other insects.

Leaf and/or foliage feeders include lemuroid, Daintree River and Herbert River ringtail possums; the larvae of the fiery jewel and bronze flat butterflies; the larvae of the moths Amphithera heteroleuca, Arignota stercorata, Echiomima mythica Parallelia constricta, Pennisetia igniflua, Pilostibes stigmatias while species of lace bug and gall-forming wasps are also associated with the foliage.

The Eungella honeyeater has been recorded feeding on the flowers and/or nectar and/or pollen.

Fruit and/or seed eaters include musky rat kangaroos, native rat species, eastern tube-nosed bats, spectacled and grey-headed flying-foxes; emus and southern cassowaries; banded, superb, rose-crowned and wompoo fruit-doves; pied imperial, topknot, whiteheaded and wonga pigeons; brown cuckoo and emerald doves; palm and sulphurcrested cockatoos; Australian king parrots, crimson and eastern rosellas; Lewin's honeyeaters, figbirds, green catbirds, tooth-billed and satin bowerbirds, noisy pittas and currawongs while the larvae of the bright cornelian butterfly bore into the seeds.

Joel Plumb

This family of tropical and subtropical trees and shrubs is predominantly rainforest dwelling.

Worldwide there are some 12 or more genera and more than 350 species. The family name reflects that of one important genus, Elaeocarpus, whose name is derived from Greek words meaning 'olive-like fruit' - seemingly more appropriate for some ELAEOCARPACEAE genera than others.

Some of the family's characteristics -

Leaves alternate or opposite, with stipules; margins entire or toothed; occasionally domatia evident. Flowers bisexual; petals 4-5 or absent altogether, often fringed; stamens numerous.

Fruits capsular in some genera, drupaceous in others.

ELAEOCARPACEAE genera in Queensland

Aceratium 5 species, all found in N.E. Queensland.

Dubouzetia I species, a small cliff-dweller found near Townsville and classified 'vulnerable'.

Elaeocarpus 25 species (5 as yet unnamed), some Q'Id species also occurring in NT and NSW.

Peripentadenia 2 species, both from N.E. Queensland, both classified 'rare'.

Sloanea 4 species, 2 Q'Id species also found in NSW.

ELAEOCARPACEAE representatives in the Rockhamton/Capricom Coast area

Elaeocarpus eumundi - usually in gallery rainforest communities

Elaeocarpus grandis - usually in gallery rainforest communities

Elaeocarpus obovatus - usually in dry rainforest communities

Elaeocarpus reticulatus - recorded from the Shoalwater Bay area

Sloanea langii - in gallery rainforest, reaching its southern distribution limit at Byfield.

Elacocrpus and Sloanea uses

Elaeocarpus and Sloanea timber is generally light-weight, soft and pale-coloured and has been used internally for furniture, flooring, joinery, plywood and lining and for case-making.

The pitted stones of E. grandis have been gathered and used to make necklaces.

The kernels of some Elaeocarpus, e.g. E. bancroftii, have been used as food by both aborigines and early settlers.

The gum of S. australis is reported to have been used in New South Wales as a stiffener for straw hats.

E. reticulatus (blueberry ash) is often cultivated as an ornamental.

Various species of Elaeocarpus and/or Sloanea provide food for mammals, birds, butterfly larvae, moth larvae and other insects.

Leaf and/or foliage feeders include lemuroid, Daintree River and Herbert River ringtail possums; the larvae of the fiery jewel and bronze flat butterflies; the larvae of the moths Amphithera heteroleuca, Arignota stercorata, Echiomima mythica Parallelia constricta, Pennisetia igniflua, Pilostibes stigmatias while species of lace bug and gall-forming wasps are also associated with the foliage.

The Eungella honeyeater has been recorded feeding on the flowers and/or nectar and/or pollen.

Fruit and/or seed eaters include musky rat kangaroos, native rat species, eastern tube-nosed bats, spectacled and grey-headed flying-foxes; emus and southern cassowaries; banded, superb, rose-crowned and wompoo fruit-doves; pied imperial, topknot, whiteheaded and wonga pigeons; brown cuckoo and emerald doves; palm and sulphurcrested cockatoos; Australian king parrots, crimson and eastern rosellas; Lewin's honeyeaters, figbirds, green catbirds, tooth-billed and satin bowerbirds, noisy pittas and currawongs while the larvae of the bright cornelian butterfly bore into the seeds.

Joel Plumb

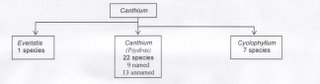

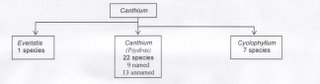

Revisions of the Canthium genus (Family RUBIACEAE) in Queensland

In 1997 the Canthium genus in Queensland consisted of 13 named and 21 unnamed species.

As a result of further studies and revisions the following changes have occurred.

Canthium has been separated into these genera primarily on the basis of differences in flower characteristics.

Nomenclature

Canthium from Canti, a Malay word for a tree in Malacca which was the first species of the genus described.

Everistia after Dr Selwyn L. Everist, a former Director of the Queensland Herbarium (1954-1976).

Cyclophyllum from the Greek cyclos meaning circle and phyllon meaning a leaf. Reference uncertain.

Some genera characteristics

Everistia Intricately branching branches (often tangled), branchlets often spiny; leaf veins absent or obscure; delicate 1-3 flowered cymes of 4-5 merous flowers; stigma deeply 2-lobed.

Cyclophyllum 1-12 flowered cymes of usually 5-merous, fleshy flowers; corolla tube long with hairs protruding from its throat; style shortly exceeding corolla tube; stigma densely clustered.

Canthium Flowers usually in branched pedunculate cymes; stigma oblongoid; style usually much exceeding corolla tube.

Species recorded in the Port Curtis Pastoral District

Name before Name now

Canthium attenuatum No change

Canthium coprosmoides Cyclophyllum coprosmoides var coprosmoides var spathulatum

Canthium lamprophyllum No change

Canthium microphyllum Everistia vacciniifolia var nervosa

Canthium odoratum No change

Canthium oleifolium No change

Canthium species (Berrigurra Station No change

E.R.Anderson 2829)

Canthium species (Larcom Gully N.Gibson) No change

Canthium vacciniifolium Everistia vacciniifolia forma vacciniifolia

Some Uses

Cyclophyllum coprosmoides The fruit is edible.

Canthium attenuatum & Canthium oleifolium Foliage regarded as good stock fodder.

Canthium odoratum The aborigines ate the ripe fruit after preparation

Recorded Wildlife Connections

Fruit and/or seed eaters

southern cassowary (Cyclophyllum)

superb fruit-dove (Cyclophyllum)

red-tailed black-cockatoo (Cyclophyllum)

moth larvae of Alucita pygmaea (C. oleifolium)

Leaf/foliage feeders

moth larvae of Balantiucha decorata (Cyclophyllum species)

Leucoptera species (Canthium species)

Lobogethes interrupts (C. oleifolium)

Macroglossum hirundo ssp errans (C. odoratum)

the bee-hawk moths, Cephonodes hylas ssp cunninghami & Cephonodes kingii (C odoratum)

Stem eaters

Moth larvae of Dudgeonea actinias (C. Attenuatum)

The swollen hollow stems of Canthium odoratum are often inhabited by ants.

Joel Plumb

In 1997 the Canthium genus in Queensland consisted of 13 named and 21 unnamed species.

As a result of further studies and revisions the following changes have occurred.

Canthium has been separated into these genera primarily on the basis of differences in flower characteristics.

Nomenclature

Canthium from Canti, a Malay word for a tree in Malacca which was the first species of the genus described.

Everistia after Dr Selwyn L. Everist, a former Director of the Queensland Herbarium (1954-1976).

Cyclophyllum from the Greek cyclos meaning circle and phyllon meaning a leaf. Reference uncertain.

Some genera characteristics

Everistia Intricately branching branches (often tangled), branchlets often spiny; leaf veins absent or obscure; delicate 1-3 flowered cymes of 4-5 merous flowers; stigma deeply 2-lobed.

Cyclophyllum 1-12 flowered cymes of usually 5-merous, fleshy flowers; corolla tube long with hairs protruding from its throat; style shortly exceeding corolla tube; stigma densely clustered.

Canthium Flowers usually in branched pedunculate cymes; stigma oblongoid; style usually much exceeding corolla tube.

Species recorded in the Port Curtis Pastoral District

Name before Name now

Canthium attenuatum No change

Canthium coprosmoides Cyclophyllum coprosmoides var coprosmoides var spathulatum

Canthium lamprophyllum No change

Canthium microphyllum Everistia vacciniifolia var nervosa

Canthium odoratum No change

Canthium oleifolium No change

Canthium species (Berrigurra Station No change

E.R.Anderson 2829)

Canthium species (Larcom Gully N.Gibson) No change

Canthium vacciniifolium Everistia vacciniifolia forma vacciniifolia

Some Uses

Cyclophyllum coprosmoides The fruit is edible.

Canthium attenuatum & Canthium oleifolium Foliage regarded as good stock fodder.

Canthium odoratum The aborigines ate the ripe fruit after preparation

Recorded Wildlife Connections

Fruit and/or seed eaters

southern cassowary (Cyclophyllum)

superb fruit-dove (Cyclophyllum)

red-tailed black-cockatoo (Cyclophyllum)

moth larvae of Alucita pygmaea (C. oleifolium)

Leaf/foliage feeders

moth larvae of Balantiucha decorata (Cyclophyllum species)

Leucoptera species (Canthium species)

Lobogethes interrupts (C. oleifolium)

Macroglossum hirundo ssp errans (C. odoratum)

the bee-hawk moths, Cephonodes hylas ssp cunninghami & Cephonodes kingii (C odoratum)

Stem eaters

Moth larvae of Dudgeonea actinias (C. Attenuatum)

The swollen hollow stems of Canthium odoratum are often inhabited by ants.

Joel Plumb

Local Melaleuca species and tips for their identification

Leaves small. usually less than 3Omm X 3mm

M bracteata (River tea-tree, Black tea-tree) - bark hard, dark, fissured - along watercourses, on lowlying flats

M trichostachya (Snow-in summer, Flax-leaved tea-tree, River tea-tree) - bark papery - along

watercourses and drainage lines.

Leaves long and narrow looking., length/width ratio 5-14 : 1

M leucadendra (Weeping tea-tree, Butterscotch paperbark) - leaves pendulous, hairless, bright green,

juvenile and adult similar - along watercourses, around swamps, in coastal sand swales

M fluviatilis (A paperbark) - leaves often pendulous, juvenile leaves hairy, narrower than adult leaves – along watercourses.

Leaves broader looking; length/width ratio 2-7: 1

Juvenile leaves with straight. silky hairs.

M viridiflora (Broad-leaved paperbark) - small tree; leaves 5-7-veined, 6cm-22cm X 2cm-6cm poorly drained or seasonally inundated near coastal flats and wallum

M quinquenervia (Broad-leaved paperbark, Paperbark tea-tree, Coastal tea-tree) - small to large tree; leaves mostly 5-veined - along watercourses, bordering swamps and on frequently wet sites

Juvenile leaves with crisped. matted hairs. the covering felt-like

M. dealbata (A paperbark) - large coastal tree with blue-grey weeping foliage; stamens less than

10mm long - between consolidated dunes and ridges behind beaches

M nervosa (A paperbark) - shrub to small tree; leaves silvery when young; stamens to 20mm long - non-swampy flats and ridges.

Joel Plumb

Leaves small. usually less than 3Omm X 3mm

M bracteata (River tea-tree, Black tea-tree) - bark hard, dark, fissured - along watercourses, on lowlying flats

M trichostachya (Snow-in summer, Flax-leaved tea-tree, River tea-tree) - bark papery - along

watercourses and drainage lines.

Leaves long and narrow looking., length/width ratio 5-14 : 1

M leucadendra (Weeping tea-tree, Butterscotch paperbark) - leaves pendulous, hairless, bright green,

juvenile and adult similar - along watercourses, around swamps, in coastal sand swales

M fluviatilis (A paperbark) - leaves often pendulous, juvenile leaves hairy, narrower than adult leaves – along watercourses.

Leaves broader looking; length/width ratio 2-7: 1

Juvenile leaves with straight. silky hairs.

M viridiflora (Broad-leaved paperbark) - small tree; leaves 5-7-veined, 6cm-22cm X 2cm-6cm poorly drained or seasonally inundated near coastal flats and wallum

M quinquenervia (Broad-leaved paperbark, Paperbark tea-tree, Coastal tea-tree) - small to large tree; leaves mostly 5-veined - along watercourses, bordering swamps and on frequently wet sites

Juvenile leaves with crisped. matted hairs. the covering felt-like

M. dealbata (A paperbark) - large coastal tree with blue-grey weeping foliage; stamens less than

10mm long - between consolidated dunes and ridges behind beaches

M nervosa (A paperbark) - shrub to small tree; leaves silvery when young; stamens to 20mm long - non-swampy flats and ridges.

Joel Plumb

Brachychitons

Belonging to the Sterculiaceae family, Brachychitons are found in Australia and Papua-New Guinea with some 30 species being endemic to Australia. B. acerifolius, B. australis, B. bidwillii, B. discolor, B. populneus ssp trilobus, B. rupestris and a naturally occurring hybrid B. x turgidulus are known to occur in the Port Curtis pastoral area.

Commonly known as kurrajongs (from an aboriginal word meaning ‘fibre-yielding plant'),

Brachychitons derive their scientific name from the Greek words brachys (short) and chiton (a coat of mail or tunic). This is a reference to the short, massed hairs around the seeds inside the fruits.

Usually trees, Brachychitons sometimes have swollen trunks e.g. B. rupestris, and are often deciduous while flowering. The leaves are alternate, simple, often large, entire or lobed, often different when juvenile and sometimes different on the same tree. Unisexual, 5 (rarely 6)-lobed, bell-shaped flowers form in axillary clusters.

Petals though absent are replaced by the petaloid lobes of the calyces. Fruiting follicles are tough and hard and split down one side to reveal numerous seeds in 2 rows separated into honeycomb-like compartments. The seeds are released gradually.

Both Aborigines and Europeans have made good use of various Brachychiton species. Aboriginal uses have included - eating young shoots, the zinc and magnesium rich seeds raw or roasted (minus the hairs), the roots of young plants raw or cooked and the gum exudate from trunk wounds; preparing an eye-wash from the inner bark of a Northern Territory species; obtaining water from the roots and making ropes, fishing nets and dilly bags from inner bark fibres.

European uses include - eating the seeds raw or roasted and chewing the mucilaginous pulp of B. rupestris for its starch; using the seeds of B. populneus as a coffee substitute (first tried by Ludwig Leichhardt); using Brachychiton foliage and the trunk pulp of B. rupestris as a drought fodder for stock (in the latter case deaths sometimes occurred from nitrate poisoning while B. populneus seeds were reportedly toxic); using the soft timber of B. acerifolius for ply and model-making and as a balsa substitute and B. populneus timber for lattice construction and interior furnishings; formerly using gum exudate to hold in dental plates; planting species such as B. acerifolius, B. populneus and B. australis as ornamentals and street trees.

Brachychiton leaves, seeds, flowers and nectar provide sustenance for many native animals. Records indicate that at least I species of possum, 24 bird species, 7 butterfly species, 5 moth species and other insect species use Brachychitons as a food source.

Joel Plumb

Belonging to the Sterculiaceae family, Brachychitons are found in Australia and Papua-New Guinea with some 30 species being endemic to Australia. B. acerifolius, B. australis, B. bidwillii, B. discolor, B. populneus ssp trilobus, B. rupestris and a naturally occurring hybrid B. x turgidulus are known to occur in the Port Curtis pastoral area.

Commonly known as kurrajongs (from an aboriginal word meaning ‘fibre-yielding plant'),

Brachychitons derive their scientific name from the Greek words brachys (short) and chiton (a coat of mail or tunic). This is a reference to the short, massed hairs around the seeds inside the fruits.

Usually trees, Brachychitons sometimes have swollen trunks e.g. B. rupestris, and are often deciduous while flowering. The leaves are alternate, simple, often large, entire or lobed, often different when juvenile and sometimes different on the same tree. Unisexual, 5 (rarely 6)-lobed, bell-shaped flowers form in axillary clusters.

Petals though absent are replaced by the petaloid lobes of the calyces. Fruiting follicles are tough and hard and split down one side to reveal numerous seeds in 2 rows separated into honeycomb-like compartments. The seeds are released gradually.

Both Aborigines and Europeans have made good use of various Brachychiton species. Aboriginal uses have included - eating young shoots, the zinc and magnesium rich seeds raw or roasted (minus the hairs), the roots of young plants raw or cooked and the gum exudate from trunk wounds; preparing an eye-wash from the inner bark of a Northern Territory species; obtaining water from the roots and making ropes, fishing nets and dilly bags from inner bark fibres.

European uses include - eating the seeds raw or roasted and chewing the mucilaginous pulp of B. rupestris for its starch; using the seeds of B. populneus as a coffee substitute (first tried by Ludwig Leichhardt); using Brachychiton foliage and the trunk pulp of B. rupestris as a drought fodder for stock (in the latter case deaths sometimes occurred from nitrate poisoning while B. populneus seeds were reportedly toxic); using the soft timber of B. acerifolius for ply and model-making and as a balsa substitute and B. populneus timber for lattice construction and interior furnishings; formerly using gum exudate to hold in dental plates; planting species such as B. acerifolius, B. populneus and B. australis as ornamentals and street trees.

Brachychiton leaves, seeds, flowers and nectar provide sustenance for many native animals. Records indicate that at least I species of possum, 24 bird species, 7 butterfly species, 5 moth species and other insect species use Brachychitons as a food source.

Joel Plumb

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)